The Son Who Could Not Come Home: Robert Todd Lincoln and the Burden of the Unfinished Epic

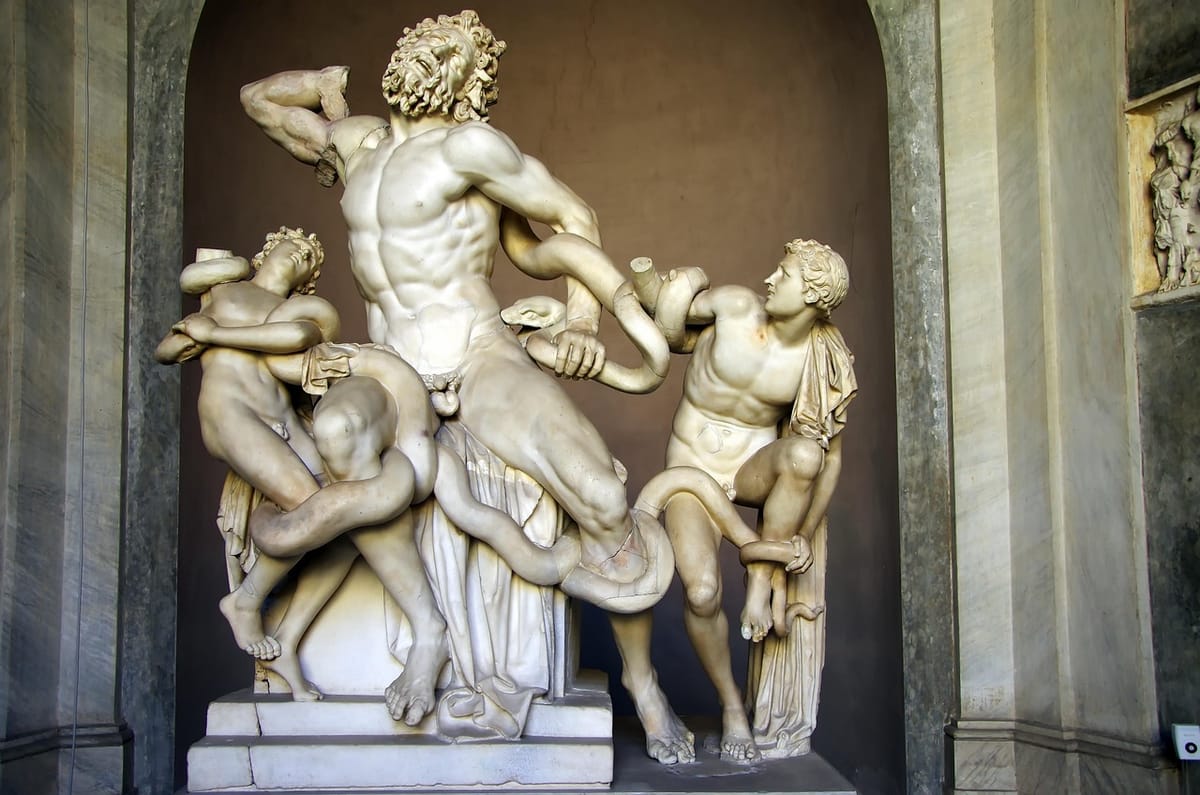

There is a particular species of American tragedy that we have not, to my knowledge, adequately named or understood. It is not the tragedy of the great man who falls from grace through hubris or moral failing: that variety we recognize easily enough, having inherited from the Greeks the vocabulary with which to discuss it. Nor is it quite the tragedy of the man who never achieves his potential; squandered gifts and unrealized promise being a subject we have never lacked for commentary upon. The tragedy I have in mind is something subtler and, in its way, more devastating: it is the tragedy of the son who is deprived of his father before any genuine transmission has occurred, and who must spend the remainder of his life carrying a name that has become not a legacy but a weight, not an inheritance but a myth he had no hand in making and no hope of escaping. It is the tragedy of the man who is asked, by history and circumstance and the expectations of a grieving nation, to be the living continuation of someone he barely knew.

Robert Todd Lincoln was such a man; and if we wish to understand him properly, I would suggest we must first turn, as one so often must when grappling with the deepest patterns of human experience, to Homer.

The Odyssey gives us Telemachus: young, uncertain, fatherless in every practical sense that matters. Odysseus is absent, the household is beset by suitors who have made themselves at home in a space that is not theirs, and the boy who would be heir must navigate a world in which his father's legendary status casts an enormous shadow without providing any of the warmth or guidance that a father's actual presence would have brought. Telemachus is not, at the poem's outset, a hero; he is a young man adrift, aware that something has been taken from him without being fully able to articulate what that something is. He knows his father by reputation, by the stories other men tell, by the residue of awe that Odysseus leaves behind wherever his name is spoken. What he does not know is his father as a man, as a presence, as a person whose habits and preferences and contradictions might help him understand his own.

Telemachus spends much of the poem searching for exactly this knowledge, traveling to Pylos and Sparta to speak with men who knew Odysseus, trying to reconstruct from fragments and memories and the admiring testimony of veterans some coherent image of the father from whom he might legitimately descend. There is a famous poignancy to his situation that ancient audiences would have understood immediately, shaped as they were by a culture in which the father-son relationship carried both personal and civic dimensions of enormous weight. The son needs the father not merely as a person to love but as a model, a legitimizing presence, someone whose return would clarify the son's own identity and purpose and rightful place in the world.

Robert Todd Lincoln needed Abraham Lincoln in precisely this way, and the need was never answered. This, I think, is where the parallel becomes genuinely illuminating and, if one allows oneself to feel it fully, genuinely heartbreaking.

Abraham Lincoln was, for most of his son's formative years, simply elsewhere. This is not a criticism of the man; the demands upon him were such as no father in American history had faced since Washington, and the nation's claim upon his time and attention was, given the circumstances, essentially total. But the fact remains that the prairie lawyer who rode the circuit for months at a time gave way, as Robert came of age, to the politician consumed by the great crisis of American life, and the boy was sent away rather than kept near. Robert spent the war years at Phillips Exeter and then at Harvard, kept from Washington by the anxious maternal protectiveness of Mary Todd, who had already lost two sons and could not bear the thought of losing another to the dangers of the wartime capital. There were visits, certainly, and letters, and whatever compressed moments of connection a president could carve out from days that belonged entirely to the republic. But these were not the sustained, daily, formative proximities through which a father genuinely shapes a son. They were interludes. They were the crumbs of a relationship that never had the opportunity to become what it needed to be.

Robert eventually made his way to Washington, commissioned as a captain on Grant's staff in the final months of the war, close enough at last to be present as the great drama reached its conclusion. He attended the theater with his parents on the evening of April 13th, 1865, and declined, through the accumulated fatigue of travel, to accompany them again to Ford's on the evening of the 14th. He came to the Peterson House when the summons arrived, and he stood in that cramped and terrible room through the long hours of the night, and he was present when his father died at twenty-two minutes past seven on the morning of April 15th. That was his homecoming. That was the moment when Odysseus returned to Ithaca: not in triumph, not to restore order and confirm the son in his rightful inheritance, not to embrace the boy who had waited and at last stand beside him as father and son fully recognized by one another, but prostrate, unconscious, attended by surgeons who could do nothing, and dead before the morning was properly underway.

The epic was over before Robert had found his proper place within it.

What makes this more than merely a sad biographical footnote is what Robert Todd Lincoln did, or rather did not do, with this deprivation in the decades that followed. Here the Homeric parallel breaks down in a way that is itself instructive, and that reveals something important about the particular nature of Robert's predicament. Telemachus, when Odysseus finally does return, becomes his father's partner in the restoration of order; he participates in the nostos, the homecoming, fights alongside his father against the suitors, and claims his portion of the resulting kleos. He grows into the story. He is transformed by the father's return from a boy in waiting into a man with a recognized identity and a legitimate claim upon the future. Robert Todd Lincoln, by contrast, spent the better part of six decades doing something very nearly the opposite: not growing into his father's story but working, methodically and with what appears to have been genuine desperation, to contain it.

He burned letters. We do not know precisely how many, or precisely which ones, because the destruction was thorough enough to ensure that we could not know. What we can say with reasonable confidence is that Robert made deliberate choices about what the historical record would and would not preserve, choices informed by a deep anxiety about what scrutiny of the Lincoln family might reveal, and perhaps equally by a desire to protect his own privacy and that of his mother, whose eccentricities and difficulties he had experienced first-hand. Beyond the burnings, he sealed the Lincoln papers at the Library of Congress against any public access until twenty-one years after his own death; a restriction that would hold until 1947. The papers he deposited there were, moreover, not the entirety of what existed; they were what he had chosen to deposit, after whatever editing and culling he judged necessary. Whatever the archive might reveal, he was determined that he would not be alive to suffer the consequences of revelation, and that a decent interval of additional years would separate whatever revelations emerged from any living person who might have known the principals.

He declined invitations, avoided commemorations, and retreated behind the walls of a highly successful but conspicuously ordinary professional life. He served as Secretary of War under both Presidents Garfield and Arthur, performing competently and without distinction of a kind that would require much commentary. He served as minister to the Court of St. James's under Harrison; a prestigious appointment and one he handled with the careful, unremarkable efficiency that characterized everything he did in public life. He then became president of the Pullman Company, the vast railroad car enterprise founded by George Pullman, and led it through the turbulent years that followed the catastrophic Pullman Strike of 1894, an episode that would bring its own moral complications and that historians have not been universally kind about. He was wealthy, by the end of all this; Hildene, the estate he built in Manchester, Vermont, was a substantial and gracious property, and he lived out his final decades there in the comfortable seclusion of a man who has arranged his life so as to be bothered as little as possible by the world's demands.

When friends and colleagues urged him toward a larger public role, toward political life and specifically toward the presidency itself, for which his name alone would have made him at minimum a plausible candidate in several election cycles, he declined with a consistency that suggests not false modesty but something approaching genuine aversion. He had seen what the presidency cost. He had watched it consume his father utterly, had understood with a clarity available to very few observers exactly what it meant to occupy that office in a time of national catastrophe, and he had then witnessed, at close and terrible range, two further presidential assassinations: Garfield's in 1881, at whose side he was present when the shooting occurred, and McKinley's in 1901, which he also witnessed firsthand. After McKinley, he reportedly refused further invitations to presidential events, remarking to friends that there was a certain pattern he had no wish to continue. Whether this was dark humor or genuine superstition or simply the observation of a man who had absorbed more trauma than any private citizen of his era, it does not much matter; the effect was the same. He withdrew, and kept withdrawing, and the withdrawals accumulated into a life.

There is something almost unbearably poignant in this, if one sits with it long enough. The man who might have been Telemachus, who might in another version of events have grown up alongside his father, been shaped by daily proximity to that extraordinary mind and character, absorbed the political education that Abraham Lincoln might have provided to a son permitted to remain near him, and been positioned to carry something genuine forward into the new century, chose instead the protection of deliberate obscurity. Where Telemachus achieves his identity by finally standing beside his father, Robert achieved his by refusing to stand anywhere near the myth that his father had become. Ordinariness, it seems, was the only refuge available to him; and he pursued it with the focused determination of a man who understands exactly what he is fleeing, and why, and what the alternative would cost.

One further element of this story demands attention, because it complicates the Homeric parallel in a way that I find both fascinating and, if I am being candid, morally troubling in its implications. In the Odyssey, Penelope holds the household together across twenty years of waiting. She is patient, faithful, and above all resourceful; her famous strategy of weaving by day and unraveling by night is not merely a delaying tactic but a demonstration of wit and agency in conditions that might have broken a less resilient person. Penelope is the anchor. She is the reason there is a household to return to. Her steadfastness is, in the poem's moral economy, the complement and the equal of Odysseus's endurance; the nostos requires them both.

Mary Todd Lincoln was not Penelope. This is not simply a biographical observation but a point of genuine structural significance for the parallel we are tracing. She collapsed into grief of a rather spectacular and eventually dangerous kind in the years following the assassination, and the grief was not of the contained, purposeful variety that might have permitted her to function as a stabilizing presence for her surviving son. She was, by most accounts of those who knew her during this period, genuinely unwell, her mental state deteriorating through a combination of genuine psychological fragility, the accumulated weight of extraordinary loss, and the socially isolating effects of widowhood in a city that had moved on more quickly than she was able to. She became, with painful inevitability, a burden and a complication for Robert, who was at the same time attempting to establish himself professionally and personally in a world that regarded him primarily as a famous man's son.

The culmination of this subsidiary tragedy came in 1875, when Robert initiated legal proceedings to have his mother declared insane and committed to a private sanitarium in Batavia, Illinois. The episode was, from any angle one cares to examine it, genuinely painful. Robert appears to have acted from genuine concern for his mother's wellbeing and safety; Mary Todd had been exhibiting behavior that alarmed those around her, and Robert was not, so far as the evidence suggests, motivated by malice or selfishness. But the proceedings were public, the trial was reported extensively in the newspapers, and the spectacle of Abraham Lincoln's son having Abraham Lincoln's widow declared mentally incompetent was not one that any of the participants emerged from with their reputations entirely intact. Mary Todd was eventually released, was never fully reconciled with her son, and spent her final years in a state of estrangement from him that must have been, for both of them, a wound that never properly closed.

Telemachus never had to become the patriarch of a household in which his mother had become ungovernable. He never had to stand in a courtroom and make the case, before the eyes of a watching nation, that the woman who had given him life was no longer capable of managing her own affairs. Robert did; and he emerged from the experience having discharged what he appears genuinely to have believed was his duty, but having done so at a cost to his public image and, one suspects, to his sense of himself that he carried for the remainder of his life.

It is worth pausing, at this point in the argument, to consider what the path not taken might actually have looked like, had history arranged itself differently. This is always a speculative exercise, and one must be careful not to confuse the historically plausible with the merely desirable; but in Robert's case the speculation is not entirely groundless, because the materials for a different life were genuinely present. Had Abraham Lincoln survived the war, had he completed a second term and returned to private life in 1869, Robert would have been in his mid-twenties with a father who was not yet sixty, vigorous, experienced, and possessed of a political intelligence that had no equal in American life. The transmission that the assassination interrupted might then have occurred. Robert might have become, under those circumstances, the kind of figure that American political history produces occasionally and prizes highly: the son who genuinely inherits his father's gifts, who carries a tradition forward rather than simply a name, who can be spoken of as a continuation rather than a footnote.

We will never know, of course, whether Robert had the gifts that such a role would have required. His professional career suggests competence and reliability rather than brilliance, and it is possible that even under more favorable circumstances he would have found his level somewhere below the heights his father had occupied. But we do not know this, and the not-knowing is itself part of the tragedy. The assassination did not merely deprive the country of Abraham Lincoln; it deprived Robert Todd Lincoln of the opportunity to discover who he might have been in his father's presence, which is a loss of a different and perhaps more intimate kind.

The truth of the matter is that Robert Todd Lincoln's life represents one of the more genuinely melancholy examples of what we might call the problem of the heroic inheritance, the peculiar burden of being born to greatness that one did not earn and cannot replicate, and being asked by the world to perform a relationship with a legend that never had the opportunity to become a genuine relationship with a man. The American path not taken, in his case, is not merely the political career he declined or the public legacy he refused to cultivate; it is something more fundamental than that. It is the question of what might have happened had the transmission actually occurred, had Odysseus come home in something other than a coffin, had the father and son had the years together that were stolen from them by John Wilkes Booth and by the relentless demands of a nation in crisis. It is the question of what Robert Todd Lincoln might have become had he been permitted, by the mercies of history, to be something other than the son of Abraham Lincoln.

We cannot know. History does not offer us that luxury, and perhaps it is right that it does not; the weight of unrealized possibility is not a burden that historical inquiry is well suited to carry, and we do well to be cautious about allowing our sympathy for the man to shade into a sentimentality that distorts our understanding of him. What we have instead is the figure of Robert Todd Lincoln as he actually was: wealthy, respected, professionally accomplished, extraordinarily private, and carrying across eight decades of life a wound so fundamental that he spent the better part of those decades working to prevent anyone, including perhaps himself, from examining it too closely. He was a man for whom the epic never properly concluded, no nostos, no restoration, no clarifying moment in which the son stands beside the father and both are recognized for what they are. He was left, instead, to manage a legend he had not made and could not escape; to be, for the remainder of his life, not quite himself, but always and primarily and inescapably the son of Abraham Lincoln.

There are worse fates, one might argue, and the argument is not without merit. To be the son of Abraham Lincoln is to carry a name that the whole of American civilization treats with something close to reverence, and there is a dignity in that, even if the dignity is borrowed rather than earned. One might argue this for quite a long time, marshaling the evidence of the comfortable life and the professional accomplishments and the years at Hildene among the Vermont mountains, and the argument would not be entirely without force.

Robert Todd Lincoln himself, I suspect, made exactly that argument, in the private tribunal of his own conscience, across the long years of his retirement. He made it in the small hours at Hildene, with the Green Mountains dark beyond the windows and the marble bust of his father presiding over the study where he sorted papers and decided what the world would and would not be permitted to know. He made it, and I think he very nearly believed it, and I think the nearness of his belief was itself the measure of how much the opposite argument had cost him to suppress. He was a man who had learned, over the course of a long and in many ways successful life, to live with the fact that the homecoming never came; that Odysseus had returned to Ithaca only to die there, in a rented room across the street from a theater, before the son had properly arrived; and that whatever life was to be built from the ruins of that unfinished epic would have to be built without the father's guidance, without the father's blessing, and with the father's myth as the permanent context within which everything Robert Todd Lincoln thought or did or was would inevitably be understood.

It was, by any measure, a great deal to ask of any son. History asked it of this one, and he bore it as well as a man reasonably could, which is to say imperfectly and at considerable private cost, and with a dignity that deserves more recognition than it has generally received from the posterity that has, on the whole, preferred to look past him toward the father he could never quite become.